“Clinton “in fact” raped Juanita”

Juanita Broaddrick Meets the Press

Wall Street Journal Column Feb. 19, 1999, page A18

by Dorothy Rabinowitz (a member of the Journal's editorial board)

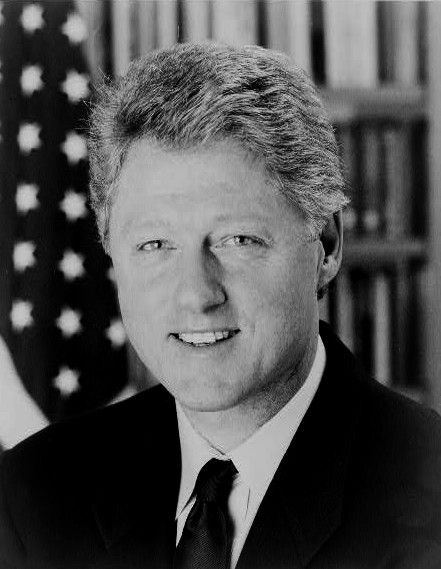

VAN BUREN, Ark.--To any reporter, it was the kind of story that doesn't come along often in a career--an alleged 1978 sexual assault involving William Jefferson Clinton, then attorney general of Arkansas. From the viewpoint of Juanita Broaddrick, it has been a trial and concern ever since reports began emerging in the 1992 presidential campaign, through the Paula Jones case and into the impeachment proceedings.

Indeed, her story was crucial to the outcome of those proceedings--just one among several reasons it is far more than another now-irrelevant Jane Doe account. It was when several wavering House Republicans read the Jane Doe material from the independent counsel's office that they decided they would vote to impeach. As Jane Doe No. 5, Mrs. Broaddrick had filed an affidavit denying that Mr. Clinton had subjected her to--as the delicately phrased document put it--"unwelcome sexual advances." Interviewed by the independent counsel's office, she said that affidavit was false, and that she had been assaulted--an account essential to understanding the second presidential impeachment in U.S. history.

Since the 1992 campaign, journalists had chased after Mrs. Broaddrick, a resistant quarry if ever there was one. With the advent of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal last year, the chase took on a new level of intensity. A Fox News crew pursued her down the highway, as she tried to outrace them at 90 miles an hour. Time magazine reporters trying to get to her pretended they were covering a local tennis benefit. The Broaddricks' phone rang incessantly with requests for interviews, all of them refused until one weekend last January.

Mrs. Broaddrick finally agreed to see NBC's Lisa Myers, who had already done a brief report on her in March and who had been calling her regularly for nearly a year. Within a day, Ms. Myers and a crew were on their way, even as an ABC producer was on the phone asking if Mrs. Broaddrick would come to New York to meet with Barbara Walters. Too late--nor was she about to vault from home, where she was surrounded by all that gave comfort and warmth, to go rushing to New York to talk about this with a stranger. It was hard enough with a reporter familiar to her.

First she had to break the news to her obdurately protective husband that, after all the years of running from the media, she had consented to go on camera. She is clear enough, in her mind, about how she had come to this decision. On New Year's Eve, as the family sat around a table celebrating with friends, someone passed around a copy of the Star, which had a report about her saying, among other things, that Mr. Clinton had bribed her husband to keep him quiet. The rest of New Year's Eve was a ruin. So was the day that followed, as she contemplated all the layers of tawdry rumor about her that had multiplied in the wake of the other, larger scandal involving the president. Perhaps the time had come, she thought, to get the facts out and put an end to all the stories, as Ms. Myers, a respected veteran reporter, had so long argued.

To encounter this woman, to hear the details of her story and the statements of the corroborating witnesses, was to understand that this was an event that in fact took place.

Still, three hours before the crew started shooting, Mrs. Broaddrick began to shake with fear as she considered the consequences, what she would be telling, and about whom. He was the president. She thought of asking if it was too late to get out of the whole thing. Still, soon enough, the camera crew had set up, the interview begun. The filming went on from midmorning to evening, and then it was over.

The interview took place Jan. 20, just over a month after the president's impeachment on Dec. 19. The Senate trial had been under way for nearly two weeks--focused, at this point, on whether Monica Lewinsky should testify. At NBC, the debate was what to do about the Broaddrick interview--a large question. NBC had scheduled the program for airing on the Jan. 29 episode of "Dateline," Mrs. Broaddrick heard--but it did not air then or later. The network had an explosive story on its hands, to be sure, and also an exhaustively investigated one. NBC's researchers had combed through the Broaddricks' entire lives, through dusty basement files and court records. "They got to read," Mrs. Broaddrick marvels, "old papers about the case we settled with two employees fired for theft 20 years ago."

As the days passed, with no Broaddrick interview--and the Feb. 12 Senate impeachment trial vote imminent--NBC News spokesmen told all callers the "Dateline" report was still a work in progress, requiring more investigation. Other sources at NBC asked--profoundly off the record--how much more confirmation could the story need? They had four witnesses giving corroborating testimony--citizens with nothing to gain and possibly much to lose by going public and talking, as the husband of one witness kept warning her. Still, they had come forward. NBC had investigated and investigated, and it was not yet enough. Word went out from NBC that the network had to cross-check dates, or lacked enough dates. Meanwhile, for any journalist asking what happened to the interview with Mrs. Broaddrick, the office of NBC News president Andrew Lack had a simple, uplifting message--namely that NBC wanted to make sure the story was "rock solid" journalism.

Mrs. Broaddrick understood her position. All she had tried to avoid by refusing all these years to talk to the press, all that she had feared--that she would not be believed, that she would be passed off as just another bimbo with a Clinton story--had now come to pass, in her view. As soon as it was evident there was to be trouble about airing the piece, she recalls, Lisa Myers told her: "The good news is you're credible. The bad news is you're very credible." Mrs. Broaddrick repeats this more than once, as though trying to puzzle its meaning--but its meaning of course is entirely clear to her, as to everyone else hearing it. It meant that to encounter this woman, to hear the details of her story and the statements of the corroborating witnesses, was to understand that this was an event that in fact took place. "Too credible" sums the matter up nicely.

It isn't hard to see what had given NBC pause. There was, first of all, the detail. Then the subject herself--a woman of accomplishment, prosperous, successful in her field, serious; a woman seeking no profit, no book, no lawsuit. A woman of a kind people like and warm to. To meet Juanita Broaddrick at her house in Van Buren is to encounter a woman of sunny disposition that the nudgings of anxiety can't quite suppress--a woman entirely aware of life's bounties. She sits talking in the peaceful house on a hilltop overlooking the Broaddricks' 40 acres, where 30 cows, five horses and a mule roam. An effervescent dog called Wally and a three-legged companion, Pearl, rush around in their midst. It is a good life all right.

The story: In 1978, 35-year-old Juanita Broaddrick--a Clinton campaign worker--had already owned a nursing home for five years. Since her graduation from nursing school she had worked for several such facilities and decided she wanted to run one of her own. It was that home that Attorney General Clinton visited one day, on a campaign stop during his run for governor. He invited Juanita, then still married to her first husband, to visit campaign headquarters when she was in Little Rock. As it happened, she told him, she was planning to attend a seminar of the American College of Nursing Home Administrators the very next week and would do just that. On her arrival in Little Rock, she called campaign headquarters. Mrs. Broaddrick was surprised to be greeted by an aide who seemed to expect her call, and who directed her to call the attorney general at his apartment. They arranged to meet at the coffee shop of the Camelot Hotel, where the seminar was held--a noisy place, Mr. Clinton pointed out; they could have coffee in her room.

They had not been there more than five minutes, Mrs. Broaddrick says, when he moved close as they stood looking out at the Arkansas River. He pointed out an old jailhouse and told her that when he became governor, he was going to renovate that place. (The building was later torn down, but in the course of their searches, NBC's investigators found proof that, as Mrs. Broaddrick said, there had been such a jail at the time.) But the conversation did not linger long on the candidate's plans for social reform. For, Mrs. Broaddrick relates, he then put his arms around her, startling her.

"He told me, 'We're both married people,' " she recalls. She recalls, too, that in her effort to make him see she had no interest of this kind in him, she told him yes, they were both married but she was deeply involved with another man--which was true. She was talking about the man she would marry after her divorce, David Broaddrick, now her husband of 18 years.

The argument failed to persuade Mr. Clinton, who, she says, got her onto the bed, held her down forcibly and bit her lips. The sexual entry itself was not without some pain, she recalls, because of her stiffness and resistance. When it was over, she says, he looked down at her and said not to worry, he was sterile--he had had mumps when he was a child. "As though that was the thing on my mind--I wasn't thinking about pregnancy, or about anything," she says. "I felt paralyzed and was starting to cry."

As he got to the door, she remembers, he turned. "This is the part that always stays in my mind--the way he put on his sunglasses. Then he looked at me and said, 'You better put some ice on that.' And then he left."

Her friend Norma Rogers, a nurse who had accompanied her on the trip, found her on the bed. She was, Ms. Rogers related in an interview, in a state of shock--lips swollen to double their size, mouth discolored from the biting, her pantyhose torn in the crotch. "She just stayed on the bed and kept repeating, 'I can't believe what happened.' " Ms. Rogers applied ice to Juanita's mouth, and they drove back home, stopping along the way for more ice.

For some time to come, Mrs. Broaddrick relates, she chastised herself for agreeing to coffee in a hotel room. "But who, for heaven's sake, would have imagined anything like this? This was the attorney general--and it just never entered my mind."

It was when several wavering House Republicans read the Jane Doe material from the independent counsel's office that they decided they would vote to impeach.

All the way home, she says, they talked about two questions: How could a man like this be governor of a state? The other, more urgent one was what to tell David, the man she loved, about the condition of her face. She decided to tell him she had been hit in the mouth by a revolving door. His answer: "That didn't happen." A few days later, she told him what had actually occurred, and it had its lasting effect. In the years that followed, they would never go to any meeting concerning nursing homes if they knew the governor would attend. Still, one day, when they ran into Mr. Clinton, he greeted them with his customary affability. This precipitated a scene wherein her husband grabbed Mr. Clinton hard, by the hand, and warned him: "Stay away from my wife and stay away from Brownwood Manor [her nursing home]." The governor, she recalls, tried to pass it off as joshing, but had to wrest himself from Mr. Broaddrick's grip.

But Mr. Clinton didn't forget her, as it turned out. In 1984, her nursing facility was judged the best in the state, which brought a congratulatory official letter from the governor. On the bottom was a handwritten note: "I admire you very much." That contact was not quite as memorable--or personal--as the one that occurred in 1991, when she was called out of a meeting concerning state nursing standards. She had no idea that the person who had summoned her was Gov. Clinton, who waited by a stairway for her. He took her hands, she recalls, and told her that he wanted to apologize, and asked what he could do to make things up to her. She said nothing and walked away. For a time, she and Norma wondered what had brought this on. Not long after, Mr. Clinton announced he was running for president.

Trouble began in 1992, when the story Mrs. Broaddrick had shared with a small circle of friends reached a wide public, thanks to a business associate by the name of Philip Yoakum. A bitter opponent of Mr. Clinton, he urged that she come forward during the presidential campaign, which she declined to do. When the Paula Jones lawsuit came along, the plaintiff's lawyers approached her, but Mrs. Broaddrick was determined to stay clear of involvement. That was how she came to sign the false affidavit.

It was this matter that the White House spokesmen and others point to when dismissing her account. Her lawyer, Republican state Sen. Bill Walters, prepared the affidavit--the model for which he says he got from White House lawyer Bruce Lindsey, who was happy to oblige. Her lawyers, Mrs. Broaddrick relates, didn't actually know the facts--that the sexual advances in question were very far from consensual. Her goal was to keep out of everything.

When Kenneth Starr's investigators came around, explains her 28-year-old son, Kevin, a lawyer, it was a different matter. "I told my mother--and she understood it--that this was another whole level. She knew it was one thing to lie in a civil trial so she could get away from all this, but another to lie to federal prosecutors and possibly a grand jury."

Fearful of punishment for that earlier perjury, she was prepared to admit to the independent counsel's officers--after receiving immunity--that her prior affidavit had been false. In the event, it became a footnote in the Starr report, and carried no weight as far as obstruction of justice charges were concerned. Both Mrs. Broaddrick and her lawyers emphasize that no one from the White House had harassed her or subjected her to other pressures aimed at keeping the story quiet.

Which does not mean the White House is rushing to facilitate any coverage of this story. Mrs. Broaddrick reports that NBC told her its investigators were waiting for the White House to answer some 40 questions relating to this matter. Asked for a response to Mrs. Broaddrick's charges, a White House spokesman told this writer yesterday that the story was so old that Mr. Clinton's personal lawyer, David Kendall, was the one to answer it. After repeated phone calls, Mr. Kendall's assistant said he was unavailable for comment.

In the meantime Mrs. Broaddrick gets intermittent calls from NBC investigators, still hanging out at the Capital Hotel in Little Rock, waiting. In the meantime, too, spokesmen for NBC News still announce their intention to make certain the story is solid--a heartening testimony to the elevated standards of journalism that have now apparently seized the network. Mrs. Broaddrick laughs, noting that NBC is still seeking answers and working on the program, which the network may one day air--an event for which she is not holding her breath.