“Clinton “in fact” raped Juanita”

Jane Doe No. 5' Goes Public With Allegation

Clinton Controversy Lingers Over Nursing Home Owner's Disputed 1978 Story

Washington Post Article Feb. 20, 1999, page A01

by Lois Romano; Peter Baker, Washington Post Staff Writers

(Read this same article on the WashingtonPost.com website.)

Her story circulated in Arkansas for years and when Bill Clinton ran for president in 1992, his enemies tried to get her to tell the world. She refused. Five years later, she opened her door to find private investigators representing Paula Jones. Still, she would not talk. "I wouldn't relive it for anything," she told them.

In the 15 months since, countless others have come calling. Agents sent by independent counsel Kenneth W. Starr. The House Republican managers prosecuting President Clinton at his impeachment trial. Reporters from around the globe. She has talked and exchanged electronic mail with scandal impresario Lucianne Goldberg and once sought advice from Clinton accuser Kathleen E. Willey. Regular updates about her are posted on the Internet and dissected on talk radio.

Now, after years of laboring to avoid the public spotlight, Juanita Broaddrick, the woman known in government documents only as "Jane Doe No. 5," has decided to speak out about her sensational yet ancient and unproven allegation that the future president sexually assaulted her in a hotel room a generation ago.

The airing of her charges has come too late to have the impact desired by those who had urged her for so long to go public, now that the Senate has acquitted Clinton at his impeachment trial and virtually assured that he will finish his term in office. But Broaddrick’s story is just one of the many loose ends of the Clinton saga that are likely to linger as he moves through the final two years of his presidency.

"It was 20 years ago and I let a man in my room and I had to take my lumps," Broaddrick said in an interview as she described why she waited so long to come forward. "It was a horrible, horrible experience and I just wanted it to go away."

It never did. Broaddrick, 55, a nursing home operator from the tiny northwest Arkansas town of Van Buren, said yesterday that she finally decided to break her public silence because there was "so much misinformation out there." In one recent example, she said, she was incensed by an account in a supermarket tabloid that reported her husband had cut a deal with Clinton to keep quiet, an assertion she dismissed as completely false.

Clinton Team's Denial

The Clinton legal team has denied her allegation as "false and outrageous" and the president's advisers in the past have noted that Broaddrick once said so herself. When Jones's attorneys first subpoenaed her in their sexual harassment lawsuit against the president, Broaddrick swore out an affidavit and testified in a deposition that Clinton did not make unwelcome sexual advances toward her in the late 1970s.

"Any allegation that the president assaulted Ms. Broaddrick more than 20 years ago is absolutely false," Clinton's personal attorney, David E. Kendall, said in a statement released by the White House yesterday. "Beyond that we are not going to comment."

Broaddrick later recanted her sworn testimony in the Jones suit under a promise of immunity from Starr, saying she lied initially because she did not want to be drawn into the case against the president. Only in recent weeks did she agree to allow reporters to quote her account. NBC News last month conducted an interview that has yet to air. The Wall Street Journal printed a lengthy piece on its opinion page yesterday. And The Washington Post was granted permission yesterday to use interviews conducted off the record starting last April.

Hers has been a story hidden in plain sight since last March, referred to in vague terms in Jones's court filings and Starr's impeachment report yet never explicitly a part of the now-concluded congressional debate over whether Clinton should be removed from office for trying to cover up his affair with Monica S. Lewinsky. Few in official Washington who have been privy to the Broaddrick story have been entirely sure what to make of it.

Starr investigated briefly but dropped it after determining that it did not fit the pattern of obstruction of justice he was investigating because she stated Clinton never tried to influence her story. House Republicans urged wavering colleagues in December to read the sealed records of Broaddrick’s FBI interview to shore up support for impeachment. And the House managers secretly contacted her to say they might summon her as a witness, yet quickly decided that her allegations were not relevant to the articles of impeachment they were prosecuting in the Senate.

Broaddrick, who owns a nursing home in Van Buren and a facility for mentally retarded children in Fort Smith, Ark., said she first met Clinton in April 1978 when he was the state's 31-year-old attorney general making his first run for governor and she was working as a volunteer for the campaign.

During a campaign stop at her Van Buren facility, she said, Clinton talked with her and invited her to visit his campaign office in Little Rock. Broaddrick, then 35, agreed to do so a week later, on April 25, while in the capital with a friend for a conference sponsored by the American College of Nursing Home Administrators. "We were very excited," she said. "We were going to pick up all that neat stuff, T-shirts, buttons."

Staying at the now-defunct Camelot Inn, Broaddrick said, she called the campaign headquarters and eventually talked with Clinton on the telephone. She later recalled he said he was not going to his headquarters that day and suggested they meet in the hotel coffee shop instead.

Arriving later in the lobby, he called and asked if they could have coffee in her room instead because there were too many reporters in the lobby, Broaddrick said. "Stupid me, I ordered coffee to the room," she said. "I thought we were going to talk about the campaign."

As she tells the story, they spent only a few minutes chatting by the window -- Clinton pointed to an old jail he wanted to renovate if he became governor -- before he began kissing her. She resisted his advances, she said, but soon he pulled her back onto the bed and forcibly had sex with her. She said she did not scream because everything happened so quickly. Her upper lip was bruised and swollen after the encounter because, she said, he had grabbed onto it with his mouth.

"The last thing he said to me was, 'You better get some ice for that.' And he put on his sunglasses and walked out the door," she recalled.

With no witnesses and the passage of so much time, Broaddrick’s story is difficult if not impossible to verify, although her husband and a friend told The Post in separate interviews that she related her account to them contemporaneously. Norma Rogers, an employee and friend who traveled with her to the conference, said that she returned to the hotel room that day to find Broaddrick badly shaken and her lip swollen. They quickly packed and left, stopping to get ice for Broaddrick’s lip on the way back to Van Buren, both later said.

Rogers, who has since moved to a suburb of Tulsa, Okla., and uses a married name, and Broaddrick said they had not talked for several years until the episode was resurrected in the Jones lawsuit. "It's true unless she has been lying to me for 20 years and I don't think she did," Rogers told The Post last spring, before the two reestablished contact. "We were close enough at the time that if something else had happened I believe she would have told me."

Rogers's family had its own unusual experience with Clinton that could affect her view of him. As governor in December 1980, he commuted the life sentence of a man, Guy L. Kuehn, who had killed Rogers's father, Ray Trentham, a school custodian, during a robbery.

Husband Supports Story

Broaddrick’s current husband, Dave Broaddrick, also backs up her story, saying she told him about the alleged encounter with Clinton days afterward. At the time, both Dave and Juanita Broaddrick were married to other people, but having an affair. They eventually married in 1981.

"I was very angry but there was nothing I could do," he said yesterday. "I was put in a very helpless situation. If it happened today, it wouldn't matter who it was, I would confront it. At the time I was not able to because of my personal situation and I have to live with that."

Otherwise, though, there is little to document the account. Separate items in the April 25, 1978, edition of the Arkansas Gazette indicated that a nursing home administrators conference was held at the Camelot Inn on that date and that Clinton had only one publicly announced event that day, an evening appearance in nearby Conway. White House officials and the state attorney general's office said they do not have records of his schedule from then and the Camelot has since closed.

Broaddrick said Clinton called her at the nursing home several times afterward but she would never take the call. The next time she recalled seeing him was in 1991, when she said she was summoned out of another nursing home meeting in Little Rock to meet with him.

"It was unreal. . . . He kept trying to hold my hand," she said. "I can still remember his words. He said, 'Can you ever forgive me? I'm not the same man I used to be.' . . . I told him, 'You just go to hell.' And I walked away. I was shaking."

Broaddrick never reported the alleged incident to authorities and said it never occurred to her to do so, because Clinton was a rising politician while she was "young and vulnerable" and in the middle of an extramarital affair.

"I had blamed myself all these years," she said. "I am a businesswoman, I made money. But I was insecure about men."

Broaddrick’s name first surfaced more than a decade later when Phillip Yoakum, a former friend who said she had confided the story in him, took it to Republican Sheffield Nelson, who lost a race for governor to Clinton. Yoakum brought Nelson to her nursing home in 1992, and they urged her to come forward, but she did not.

Jones's lawyers heard about her from another Republican activist in Arkansas who led them to Yoakum. After their private investigators visited Broaddrick on Nov. 13, 1997, her lawyer, Bill Walters, a Republican state senator, contacted a Clinton lawyer and asked for a draft affidavit for her to sign denying the "rumors and stories" about her and Clinton. "These allegations are untrue," she said in the Jan. 2, 1998, affidavit, "and I had hoped that they would no longer haunt me or cause further disruption to my family."

Unswayed, the Jones team used an uncorroborated letter from Yoakum to raise the allegation in court filings last March 28, just days before a federal judge dismissed the lawsuit.

Starr's Inquiry

FBI agents working for Starr then approached Broaddrick and after being promised that she would not be prosecuted for perjury she disavowed her previous sworn testimony without getting into details, sources have said. Starr made note of her change of heart in a passing reference in an appendix sent to the House along with his Lewinsky impeachment referral. The FBI interview, which deemed her account "inconclusive" according to the sources, has never been made public, although a variety of House Republicans read it in a sealed room before voting to impeach Clinton on Dec. 19.

The House Judiciary Committee Republicans who would handle Clinton's prosecution in the Senate first got in touch just after Thanksgiving. Rep. Asa Hutchinson (R-Ark.), who knew Walters from GOP political circles, met with Broaddrick, focusing not on the alleged assault but on whether anyone tried to silence her.

The House team later sent two investigators to meet with her. And another manager, Rep. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), had "a five-minute conversation" with Broaddrick but also told her she would not be relevant to the trial.

"From my standpoint, I think it was appropriate behavior on our part," Hutchinson said. They never pressed to include the Broaddrick allegation in the trial, he added, because "it would have been wrong to throw out something pejorative to the president and not probative to the issues involved."

The Discussion Spreads Although her allegation had been covered in the news media sporadically, it became the subject of widespread discussion in political and journalistic circles in mid-January, when NBC News correspondent Lisa Myers conducted a videotaped interview with Broaddrick at her Van Buren home. Word of that interview was leaked to Internet columnist Matt Drudge, whose report triggered thousands of calls to NBC from viewers angry that the account had not been broadcast.

Fox News Channel later reported the allegations, but without an interview with Broaddrick. As the president's impeachment trial moved toward a verdict, the Broaddrick controversy was all over the Internet and talk radio and was mentioned on some cable talk shows.

Her version of the allegations emerged publicly for the first time yesterday when Dorothy Rabinowitz, an editorial writer on the Wall Street Journal's conservative opinion pages, published a lengthy account of her interviews with Broaddrick last week, granted after Broaddrick grew frustrated with NBC's hesitation.

"Juanita has never been in control of this story," Dave Broaddrick said yesterday. "She told it when she has had to in legal situations. This is the first time, under no pressure, she has been able to be in control of the story since it happened, and that's a refreshing place to be."

Looking back, Juanita Broaddrick said yesterday that she does not believe she made a mistake by keeping quiet in 1978 but wishes she had come forward in 1992. "I feel that had I come out in '92, that it may have made a difference," she said. "I regret that."

As for going public now, she said, "I feel like I have gotten the biggest weight off my shoulders. I did it because of my twin granddaughters -- they're 12. . . . When they ask me about this in a few years, I want them to say, 'That was a neat thing you did.' I didn't want them asking me, 'Why didn't you come forward?' "

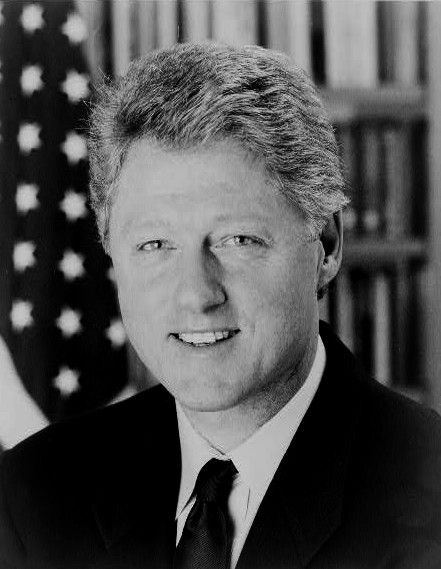

Staff writers Lorraine Adams, Charles R. Babcock, William Claiborne, Juliet Eilperin, Guy Gugliotta, Howard Kurtz and Susan Schmidt and staff researchers Nathan Abse and Alice Crites contributed to this report. Juanita Broaddrick, right, poses at nursing home in Van Buren, Ark., with residents and Bill Clinton, then attorney general and gubernatorial candidate.

Second Washington Post Article That Ran The Same Day Eight Pages Later:

A Long-Simmering Story Explodes Into the Mainstream

Washington Post Article Feb. 20, 1999, page A09

by Howard Kurtz, Washington Post Staff Writer

Under pressure from angry viewers, NBC News has wrestled for weeks with whether to air an exclusive interview with an Arkansas woman who has accused President Clinton of sexually assaulting her 21 years ago.

NBC correspondent Lisa Myers got the first on-the-record interview with the woman last month, but NBC News President Andrew Lack and his top deputies have yet to run the story, maintaining that the network lacks sufficient corroboration of the woman's allegations.

Yesterday, the accusations exploded into public view when Dorothy Rabinowitz, a Wall Street Journal editorial board member, published her own account of a lengthy interview she had with the woman, Juanita Broaddrick Broaddrick. But NBC is still holding back its taped interview.

"There are moments in your life when you know . . . you know this is not a story that should be suppressed," Rabinowitz said yesterday. Broaddrick, she said, "is wealthy. There's no motive to lie. She's done nothing but hide from the press."

The differing approaches reflect the struggle of a number of news organizations, including The Washington Post, to deal with a delicate, long-ago allegation that could have affected the president's impeachment trial had it been carried in the mainstream press. What made this period extraordinary was that millions of people knew, largely through the Internet, the general outlines of Broaddrick’s allegation.

Several NBC sources said Myers and her Washington bureau chief, Tim Russert, were frustrated by their inability to get the story on the air. They and other advocates believe that each time they came up with further corroboration, NBC management raises the evidentiary bar a little higher. They also feel badly about winning Broaddrick’s trust, combing through her records and disrupting her life, only to keep holding the story, these sources said.

Myers, who has pursued Broaddrick for a year, would say only that the story "remains a work in progress. We learn something new every day." An NBC executive said that "there are some serious aspects of it that are still unable to be confirmed."

But Broaddrick eventually grew frustrated and agreed to talk to the Journal.

"I feel so betrayed by NBC," Broaddrick said yesterday. Her son, Kevin Hickey, said Myers had assured them after the taping that there was no chance the interview would not run as scheduled on Jan. 29. NBC also interviewed a friend of Broaddrick’s who saw Broaddrick after the alleged assault and confirmed her account.

One question giving NBC pause is its failure to obtain a record placing Clinton at a Little Rock hotel where Broaddrick says the assault occurred on that day in 1978.

Several major news organizations, including The Post, reported the outline of the charge by "Jane Doe No. 5," as Broaddrick was called, when Paula Jones's attorneys included it in a court filing last March. Myers was one of the few journalists to identify Broaddrick by name. But the story was clouded because Broaddrick had denied the assault in an affidavit, which she would later retract after being contacted by independent counsel Kenneth W. Starr's office.

NBC has been deluged with telephone calls and e-mail since last month, when Internet columnist Matt Drudge reported that the network was holding Myers's interview. Jerry Falwell asked his followers to "inundate" the producer of "NBC Nightly News" with calls of complaint. Many people accused the network of bowing to White House pressure, though NBC officials say there was no such pressure.

Fox News Channel soon reported the Broaddrick allegations and NBC's role, with long-distance footage of her leaving a tennis club. "I didn't think it was a particularly hard call," said Brit Hume, Fox's Washington managing editor. "It was one of those cases where everyone knows the deal but readers and viewers. . . . She is telling a story that is relevant to what sort of man this is . . . which is what the Monica Lewinsky story is about." Hume once wore a "Free Lisa Myers" button on the air.

Washington Post reporter Lois Romano interviewed Broaddrick numerous times, but "the interviews we had conducted were off the record and we were not released from that pledge" until she went public elsewhere, Executive Editor Leonard Downie Jr. said. "We began working on corroboration, and that process was still ongoing." Downie noted that The Post reported in December that House Judiciary Committee Republicans were urging fellow GOP lawmakers to read the sealed evidence involving Jane Doe No. 5 -- but that FBI interviewers had found her account "inconclusive."

The New York Post ran a story Feb. 3, followed by a front-page Washington Times account the next day. The allegations spread as they were cited in further Drudge reports, on other Web sites and on talk radio, as well as in the current issue of Newsweek. On MSNBC, Rep. Chris Cannon (R-Utah) told an anchor: "Everybody knows in Washington, D.C., that your colleague Lisa Myers has Jane Doe No. 5 on videotape and you haven't broken the story."

Despite the Journal report yesterday, NBC sources say, network executives feel they must stick by their earlier position, even if the story is breaking elsewhere.

Rabinowitz said she showed up in a limousine at Broaddrick’s ranch in Van Buren, Ark., for a story on the media's handling of the matter and wound up talking to Broaddrick for two days. "I am not a hard-news reporter," Rabinowitz said. "I really don't like banging on people's doors. . . . We were just hanging out. Then I got the rest of the story. . . . I said, 'Do you mind if I quote that?' She said, 'No, go ahead.' "

The Journal maintains an unusually steep wall between its newsroom and its conservative editorial page, which has denounced Clinton for six years and published books about Whitewater. Editorial Page Editor Robert Bartley said he did not tell any news editor he was publishing Broaddrick’s charges.

"To be sure, you want something that seems reasonable and credible," Bartley said. "But you don't hold a trial before you publish a news story."

Gerald Seib, deputy chief of the Journal's Washington bureau, said last night that he was not alarmed by the editorial page's decision not to alert the newsroom to the story. "They do what they do and we do what we do. It always surprises people, but that's the way it's always been. We wouldn't expect to know about it."

Third Washington Post Article Ran Eleven Days Later to Close the Matter:

No Rest for the Scandal-Weary

Washington Post Article Mar. 1, 1999, page C1

by Howard Kurtz, Washington Post Staff Writer

Now that Juanita Broaddrick has made her accusation against President Clinton on national television, the question naturally arises: Where does the press go from here?

The conventions of journalism generally require a second-, third- or fourth-day lead, some legal or investigative machinery to propel the story line forward. But Clinton's already been impeached and acquitted, and the Paula Jones suit is settled. So Broaddrick’s tearful account of a 21-year-old sexual assault, denied by Clinton's attorney, sort of hangs in the air.

Ordinarily, an allegation dating to 1978, with no police or medical records, would fall outside the journalistic statute of limitations. Many reporters, like much of the public, are suffering from scandal fatigue. But the seriousness of the charge made it difficult for the news outlets that interviewed Broaddrick to dismiss. And some commentators have questioned the lack of a detailed defense -- even a personal denial -- by the president.

The White House has refused to say whether Clinton acknowledges any relationship with the Arkansas woman, or even whether he was in the same Little Rock hotel on the day she says she was assaulted. And fairly or unfairly, Clinton's false, finger-wagging denial of a sexual relationship with Monica Lewinsky has boosted the normal level of media skepticism.

The Broaddrick allegation has followed a rocky path, causing considerable turmoil within NBC as network executives refused to run correspondent Lisa Myers's interview for more than a month. Angry viewers around the country accused NBC of "suppressing" or "censoring" her story; there were even unfounded suggestions of a cave-in to White House pressure.

Apparently these viewers fail to understand that journalists must try to corroborate charges before throwing them on the air. Still, cautious NBC executives waited until the coast was clear -- after Broaddrick’s allegation had already been reported by the Wall Street Journal editorial page and The Washington Post.

"There were honest differences of opinion as to whether NBC should run a story about a rape allegation about the president of the United States from 20 years ago when we simply cannot prove it," Myers said on MSNBC.

The media queasiness continues; ABC, while posting its own Broaddrick interview online, has not reported it as an on-air news story. "We feel there is no development beyond the fact that her name has been made public that warrants additional coverage," said spokeswoman Eileen Murphy.

But many editorial pages have been harsh. If the accusation is true, the Philadelphia Inquirer says, Clinton "is a sick man who needs psychiatric care." Says the Chicago Tribune: "Given Bill Clinton's known capacity for boorish and immoral sexual behavior, the charge does not seem incredible. And that is unnerving."

Should the story have been reported at all? In 1991 the press pounced on an allegation by a former aide to Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas that Thomas had sexually harassed her eight years earlier. Anita Hill had never complained before and had followed Thomas to a second job. If her story was news -- and Hill never accused Thomas of laying a finger on her -- how can Broaddrick’s far more serious charge not be?

The Washington Post ran Juanita Broaddrick's false affidavit, as follows:

Affidavit From Jane Doe #5

Wednesday, December 23, 1998

Editor's Note: Following is the text of a Jan. 2, 1998, affidavit from the woman known as "Jane Doe No. 5." The Paula Jones legal team in a March 28 filing reported an unsubstantiated hearsay claim that, 20 years ago, Clinton had invited Jane Doe No. 5 to a hotel room and forced her to have sex. This affidavit, in which the woman denies the claim, was released by the Clinton legal team in its March 30 filing (see the Post story).

1. My name is Jane Doe #5. I am 55 years old and have been married since 1981. I have one child, age 28. I currently reside in Arkansas.

2. In November of 1997, two private investigators retained by Paula Corbin Jones approached me at my residence. I declined to speak with them, but provided the name of my family attorney. I subsequently was served with a subpoena seeking the production of documents and purporting to require my testimony at a deposition in the civil action between Paula Corbin Jones and President William Jefferson Clinton (Civil Action No. LR-C-94-290). I have never met Ms. Jones, nor do I have any information regarding the allegations that she has advanced against President Clinton. In this regard, I have no knowledge or information regarding the events she has alleged occurred on May 8, 1991 at the Excelsior Hotel or, for that matter, any knowledge or information regarding any interaction between herself and Mr. Clinton.

3. I met President Clinton more than twenty years ago through family friends. Our introduction was not arranged or facilitated, in any way, by the Arkansas State Police. I have never been an Arkansas state employee or a federal employee. I have never discussed with Mr. Clinton the possibility of state or federal employment nor has he offered me any such position. I have had no further relations with him for the past (15) years.

4. During the 1992 Presidential campaign there were unfounded rumors and stories circulated that Mr. Clinton had made unwelcome sexual advances toward me in the late seventies. Newspaper and tabloid reporters hounded me and my family, seeking corroboration of these tales. I repeatedly denied the allegations and requested that my family's privacy be respected. These allegations are untrue and I had hoped that they would no longer haunt me, or cause further disruption to my family.

5. I do not possess any information that could possibly be relevant to the allegations advanced by Paula Corbin Jones or which could lead to admissible evidence in her case. Specifically, I do not have any information to offer regarding a nonconsensual or unwelcome sexual advance by Mr. Clinton, any discussion offer or provision of state or federal employment or advancement in exchange for sexual conduct, or any use of state troopers to procure women for sex. Requiring my testimony at a deposition in this matter would cause unwarranted attorney's fees and costs, disruption to my life and constitute an invasion of my right to privacy. For these reasons, I have asked my attorney to advise Ms. Jones's counsel that there is no truth to the rumors they are pursuing and to provide her counsel with this sworn affidavit.

Further affiant sayeth not.

Jane Doe #5